Tectonics and Growth

My wife is reading Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast and Slow”, somewhere in which he relates his reaction when he first came across the bedrock of mainstream economics: rational microeconomic behavior. I must admit I had a very similar reaction. The description of human behavior that underpins modern economics is so bizarre that my first thought was that it must be some form of Monty Pythonesque satire. Surely, I thought, this is a joke and in a few pages all will be revealed. But no. Economics really is built on a foundation that to outside eyes is not just odd, but what appears to be a deliberate spoof.

What is even more strange, and those of you who listen to economists and take them seriously please suspend your sense of humor at this point, is that this total perversion of humanity is then taken as the essential starting point for all subsequent theorizing. Economists are all brought up nowadays to repeat the mantra that all “good” theorizing about the economy at higher levels — what economists call macroeconomic theory — has to be based on a foundation of theorizing at a lower level — what economists call microeconomics. So in the literature and in conversation it is common to come across the phrase that some higher level idea is based upon “micro foundations”.

Except that foundation is exactly what Kahneman and others laugh at.

You would too if you spent any time at all thinking about it.

Which brings me to another point: economics is full of these oddities that anyone outside the profession would dismiss a priori as some form of ludicrous joke.

Take general equilibrium. You may have heard of it. Economists love to talk about equilibrium. It’s one of those early importations from 19th century physics that economists took on board so as to make their work look more scientific. And it fits neatly with Adam Smith’s casual observation that an economy appears to exhibit a mysterious sort of order. My interpretation of Smith is that he was simply saying that stuff seems to get done, and isn’t that wonderful. Unfortunately subsequent economists turned his almost flippant comment into a sort of holy grail and started looking for ways to prove the existence of such a general equilibrium. Their final triumph came with what is known as the Arrow-Debreu work not long after World War II, with that work proving the existence of a configuration of the economy that is indeed a general equilibrium. For those of you whose eyes are glazing over at this moment: economics has two sorts of equilibrium, one is “partial” in which stuff still is in motion in a general sense, but a small isolated sliver of the economy appears to have reached a nice balance; the other is “general” in which the entire economy has arrived at such a nice balance. Whilst partial equilibrium is sort of sensible because it is easy to understand that a small sliver of an economy could be in a balance, the idea that entire economy could end up in such a magical place is, well, magical.

Anyway, and here’s the satire, the so-called proof of general equilibrium is so ridiculous and other-worldly that no one in their right mind could ever take the concept of general equilibrium seriously. Even Ken Arrow, of Arrow-Debreu fame, said as much. But economists do. Yes they actually study it. Perhaps they study unicorns too.

One consequence of economics being packed full of all this self-satirical nonsense is that it has great difficulty in explaining real world situations. The entire body of thought of economics includes useful tidbits that anyone can pick up and play with because they are common-sensical. But when we rely on economics to explain big important questions it begins to stutter and creak under the weight of all that absurdity.

Which is why it fails to explain long term, or what I call tectonic, shifts.

Remember that economics only as recently as the late 1980’s bothered to contemplate technology as a factor explaining growth. You and I, steeped as we are in real world experience may have taken on board the idea that maybe, just maybe, technology was vaguely related to growth. Indeed we probably took it for granted. But economists arrived at that particular idea a full century and a half into the technological explosion we grandly call the Industrial Revolution. Up until the late 1980’s economists simply looked at technological change as something that sort of happened outside an economy.

Let me give you another example: economics had a hard time explaining economic growth at all until Robert Solow invented something called “Growth Theory” in the 1950’s. And even his breakthrough, which is treated, properly in the context, with awe and monumental respect inside the profession, left giant chunks of growth unexplained. Naturally economists came up with jargon to describe this unexplained chunk — they called it “Total Factor Productivity” — which is another of those spoofs I mentioned above. For all their subsequent efforts, including the aforementioned sudden realization that technology might have something to do with it, economists are still at sea when asked to explain growth, why it suddenly took off in the late 1800’s, and why it might be slowing down now.

This is all very relevant because we are now in a moment when growth rates in economies are very much a political topic. Here in the US, Trump made a big deal of it in the election. Worldwide there is much hand wringing over the possibility that we have fallen into stagnation and that all that fast growth since 1870 is now over. The socio-economic and socio-political consequences of stagnation as a longer term reality are enormous, and it would be nice if economics could say something other than wallow around in its self-satirical references to equilibrium and rationality.

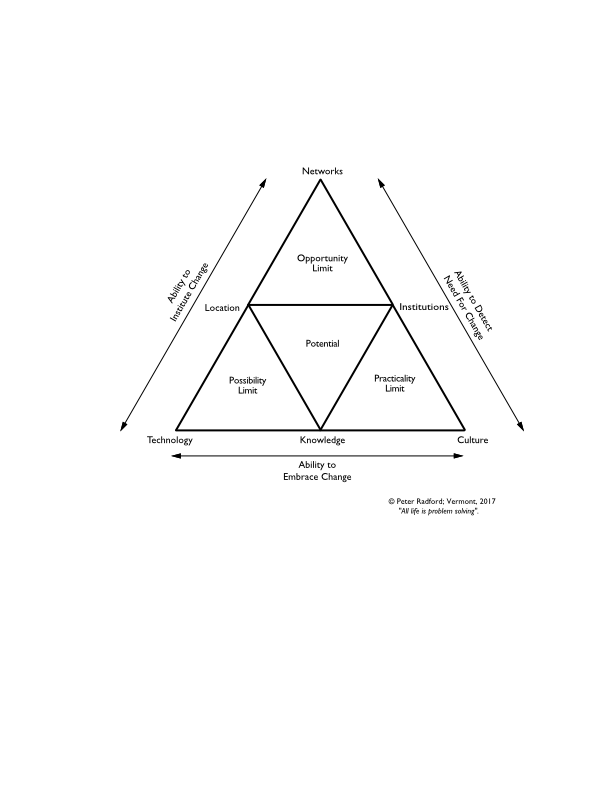

So, in the spirit of helping you frame your own thoughts about growth, and to help you ponder the tectonic shifts underway down beneath the froth of the surface phenomena of economics, here is the diagram I keep in front of me to remind where to look for problems and solutions. It is not a theory, it is a framework:

I apologize for the poor presentation, I haven’t reduced that file size for years. But this is the way I have been looking at growth since that late 1990’s. I will devote more time to it in future.

Meanwhile: chin up. This too shall pass.